Tom Bombadil is one of the most enigmatic characters in

J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. Many have speculated on the

true nature of Tom Bombadil. Although their explanations have their

strong and weak points, none are truly convincing. I believe, however,

that most speculators have been too narrow in their thinking; a true,

convincing explanation of Tom Bombadil depends on one considering the

history of Middle Earth in its proper context.

Most theories about Bombadil’s nature are based on large part on the

ancient Elvish folklore published in The Silmarillion. But The

Silmarillion is mythology. To be sure, The Silmarillion is more

factual than a typical mythology, seeing that many eyewitnesses of the

events in it remained alive in Middle Earth through the War of the

Ring. Nevertheless, it is a mythology: and we cannot trust its literal

truth.

The literal truth of The Silmarillion is most doubtful in the

stories of the Valar, for The Silmarillion is a tale written by

Elves, yet many stories concerning the Valar predated their

existence. Stories of the early wars between the Valar and Melkor

(before the First Awakening) are dubious, as are stories of the

origins of the Sun, the Moon, and the stars. Such stories, which

explain the existence of things hard to explain, are always dubious in

mythology. Other stories, such as the story of the two trees,

Telperion and Laurelin, how Orcs came to be, and Earendil’s voyage,

are likely exaggerated.

Furthermore, even if we accept that the Valar simply told the Elves

what happened before they were born, we can’t expect the natural

beings like the Elves to be able to comprehend the methods of

supernatural beings like the Valar. Most likely, the stories of the

Valar are metaphorical, rather than literal, accounts.

The point of this, as it relates to Bombadil, is that the early

stories of Middle Earth are often very doubtful, and may only contain

metaphorical truths. Yet, many of the beings Bombadil is theorized to

be (Valar, Maiar, Iluvatar) are explained fully only in The

Silmarillion.

Furthermore, many theories try to place Bombadil in the context of

early Earth, as described in The Silmarillion, to justify

themselves. (For example, a theory might place Bombadil on Earth while

the Valar lived on the Isle of Almaren, in order to claim that

Bombadil is himself a Vala. This, even though the very existence of

Almaren is questionable.) Such theories are flawed, because they

accept the literal reality of the tales.

The key to explaining what Bombadil is to not take The Silmarillion

too literally. Instead, we consider the Earth in its context as we

know it today.

The following passage is the most significant clue about Tom’s

nature. This is his answer to Frodo’s question, “Master, who are you?”

(LOTR 129):

Eldest, that’s what I am. Mark my words, my friends: Tom was here

before the river and the trees; Tom remembers the first raindrop

and the first acorn. He made paths before the Big People, and saw

the little People arriving. He was here before the Kings and the

graves and the Barrow-wights. When the Elves passed westward, Tom

was here already, before the seas were bent. He knew the dark

under the stars when it was fearless – before the Dark Lord came

from Outside.

One interesting thing Tom says is that he remembers the first

raindrop; this means Tom actually predates the world in its current

form. Almost all life on Earth needs water; therefore, we assume Tom

predates life as well, at least life on land. Tom implies this when he

says he remembers the first acorn. Also, he claims he was there before

the river; was he there before the ocean, too?

Bombadil also calls himself the “Eldest.” He was not the only person

to do this: in the Council of Elrond, Glorfindel calls him the “First”

(LOTR 259). Why do these High Elves call Bombadil the “First,” when

many of whom supposedly dwelled in the Far West, along with the Valar

who were supposed to be the first? It is clear that the Elves believe

Bombadil was on the Earth since it’s earliest days, even before the

Valar lived on the Earth, and even before the Earth was in the form it

is today.

The Ainulandale, although myth, provides more evidence of this, if

we accept the chronology of the world’s formation that it

describes. Iluvatar, speaking to Ulmo before the Ainur entered the

world, says to him, “Behold rather the height and glory of the clouds,

and the everchanging mist; and listen to the fall of rain upon the

Earth!” (Silm 19). As we said, Bombadil claims he saw the first

raindrop; therefore, if the chronology in Ainulandale is accurate,

Bombadil was on the Earth before the Valar.

But what, exactly, is the “Earth”? Previous theorists have

automatically accepted the account of the Earth in The Silmarillion,

i.e., that it was created flat, that Melkor messed everything up so

the Valar moved to the Uttermost West, and that Eru bent the flat

Earth into a round sphere when the Numenorians attacked Aman.

However, as my theory treats The Silmarillion as mythology, it

cannot do that. Consider the different perspectives of the Elves and

us. To the Elves, the Earth was the whole Universe. To us, the Earth

is a small planet in an unimaginably vast space. Elves often use the

Earth to refer to the everything that exists, because, to the Elves,

the Earth was everything. We, however, have to distinguish what sense

the Elves referred to the Earth in: did they mean “this big hunk of

rock we walk on” or “everything that exists; the whole Universe”?

Accordingly, when the Elves speak of the Early Days of Earth (“the

Springtime of Arda”), do they mean the early days of the big hunk of

rock we walk on, or the early days of the universe?

My theory is, when the Elves called Bombadil the “First,” and when

Bombadil calls himself the “Eldest,” they mean he is the first and

eldest in existence. The Elves might have no idea that existence could

predate the Earth, but when they say “Bombadil is the First,” the mean

Bombadil is the First, i.e., the first to exist anywhere. Bombadil,

on his part, might never mention the days before Earth existed, so as

not to confuse anyone.

So, if this is true, it means that Tom existed from the Universe’s early days. In this case, it becomes clear what Bombadil is. There is only one good explanation: Tom Bombadil is the Dark Matter making up 90% of the mass of the Universe.

If the Powers are the Valar (after all, “vala” means “power” in High

Elvish), and the Beautiful Ones are the Maiar, then Bombadil would be

called a Morerma (or better yet, The Morerma, as there is certainly

only one of him).

I suppose you’re thinking, “How can Tom Bombadil himself make up 90%

of the mass of the universe? Wouldn’t his gravitational pull instantly

swallow the whole galaxy?” Well, obviously, he’s not all of the Dark

Matter. In fact, his body might not actually consist of Dark Matter,

although considering his foot speed, there’s a good chance that it

does. It is clear, however, that Bombadil is associated with the Dark

Matter.

Exactly what the association is can’t be answered. Perhaps Bombadil is the Dark Matter, or maybe the Dark Matter is Bombadil? Perhaps the Dark Matter is the real Being, and Bombadil is just his Earthly raiment. Or, maybe Tom Bombadil is the Master of the Dark Matter. We can’t be certain; but we do know that the same spirit that rests in Bombadil also rests in the Dark Matter; they are parts of the same being.

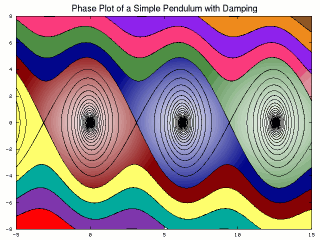

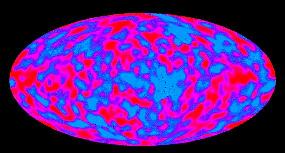

At the right is a picture of the cosmic background radiation; essentially this is a panoramic view of the Universe in its earliest stages. This image shows Bombadil hard at work, as he brings about the formation of the Universe’s first macroscopic structures. These formations eventually led to the condensation of the universe, which in turn allowed the formation of stars and planets.

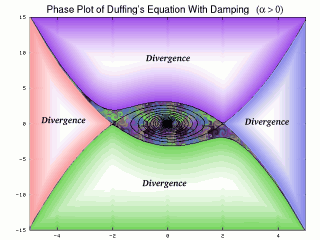

This photograph shows Tom Bombadil obstructing an edge view of a galaxy. Many models predict the presence of Dark Matter on the rims of galaxies. Much as on Middle Earth, Bombadil is faster than the fast: the Dark Matter orbits the galactic core faster than the stars inside. (And lest you think I need to brush up on my orbital mechanics, let me say your objection is almost certainly wrong. Surely you mean to point out that objects further from the center of gravity orbit slower? Well, not in this case. Because the galaxy is densely populated with stars, gravity cancels out close to the center. Therefore, stars near the center orbit slower than the Dark Matter on the outside. Indeed, Bombadil’s feet are faster.)

Anyways, this is just a theory, but a theory I feel is more convincing

than current theories because it is based in fact, not mythology. It’s

not cop-out like those “nature spirit” or “non-Vala, non-Maia Ainu”

theories, because it explains the very nature of Tom Bombadil and his

purpose.

Works Cited

[LOTR] Tolkien, J. R. R. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton

Mifflin, 1993

[Silm] Tolkien, J. R. R. The Silmarillion. Boston: Houghton

Mifflin, 2001